It’s shortly after dawn when Edward Lawson, one of America’s 3.2 million public school teachers, pulls his car into the parking lot of Julian Thomas Elementary in Racine, Wisconsin. He cuts the engine, pulls out his cell phone and calls his principal. They begin to pray.

Lawson is a full-time substitute based at a school with full-time problems: only one in 10 students are proficient in reading and math.

That may be explained by the fact that 87 percent of the students are poor and one in five have a diagnosed disability. Blame for test scores, however, often settles on the people who are any school’s single-most-important influence on academic achievement – teachers.

Lawson says a prayer for the coming school day. He says a prayer for the district, the students, the upcoming state tests. He says a prayer for the second-grade teacher who had emergency back surgery and for the sub taking her class.

He says a prayer for all teachers – a fitting petition for a profession in crisis.

The crisis became manifest this spring when teachers in six states, sometimes even without the direction or encouragement of any union, walked off the job to protest their own compensation and school spending in general.

We think we know teachers; we’ve all had them. But the suddenness and vehemence of the Teacher Spring suggest we don’t understand their pressures and frustrations.

To try to understand, 15 teams of USA TODAY NETWORK journalists spent Monday, Sept. 17, with teachers around the nation.

We found that teachers are worried about more than money. They feel misunderstood, unheard and, above all, disrespected.

That disrespect comes from many sources: parents who are uninvolved or too involved; government mandates that dictate how, and to what measures, teachers must teach; state school budgets that have never recovered from Great Recession cuts, leading to inadequately prepared teachers and inadequately supplied classrooms.

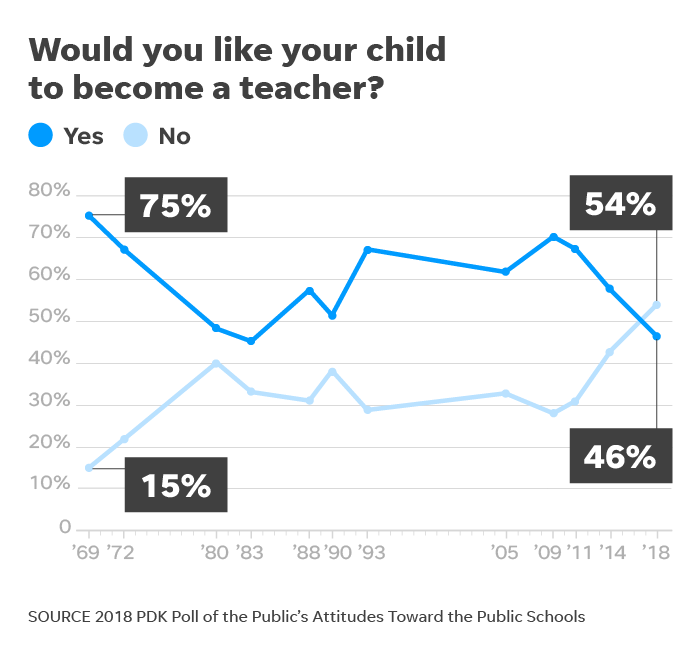

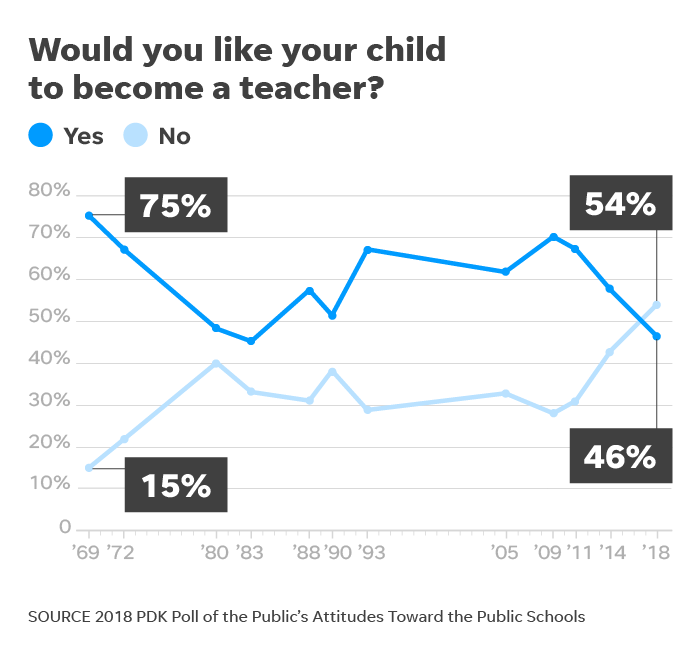

It all may be exacting a toll. This year, for the first time since pollsters started asking a half-century ago, a majority of Americans said they would not want their child to become a teacher.

Yet teachers everywhere say that if only the American people – the parent, the voter, the politician, the philanthropist – really understood schools and teachers, they’d join their cause.

Some people mistakenly think teachers “sit around all summer, collecting a paycheck,’’ complains Lawson, the full-time substitute. Not him. In addition to working in both the before- and after-school programs, he teaches summer school and last summer took on extra hours at an Amazon warehouse.

Lawson is a jack of all trades. A walkie-talkie on his hip, he moves from room to room — teaching a class or organizing a lesson plan for a short-term sub or giving students special help with math. He visits homes with the school social worker. He directs traffic in the parking lot. He once used the washing machine in his office to clean the coats of an entire class so he wouldn’t embarrass the one kid whose coat was filthy.

Despite it all – or maybe because of it – he voices a claim made by virtually every teacher with whom a USA TODAY NETWORK team spent the day: He loves his job. “I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. When you help a kid that really wants to learn, when they say, ‘I got it,’ that’s something you take with you the rest of your life.”

A crisis in perspective

Public school teachers’ economic prospects have worsened dramatically since the beginning of the Great Recession, especially in poorer states.

The average national salary has decreased by more than 4 percent since 2009, adjusted for inflation. Yet nine in 10 teachers buy some of their own teaching supplies, spending an average of almost $500 a year.

About 18 percent have a second job, making teachers about five times more likely than the average full-time worker to have a part-time job.

No surprise, then, that 8 percent of teachers leave the profession each year, compared with 5 percent a few decades ago; that 20 to 30 percent of all beginning teachers leave within five years, the Learning Policy Institute says, and two-thirds of teachers quit before retirement; that enrollment in college teacher education programs dropped 35 percent between 2009 and 2014.

The result, in some areas and in some specialties, is a teacher shortage. Last year, according to a Learning Policy Institute study, more than 100,000 classrooms were staffed by instructors “not fully qualified to teach’’ because they lacked proper licenses or degrees. The percentage of teachers working without bachelor’s degrees, although small (2.4 percent in 2016), has more than doubled since 2004.

Those are the numbers, based on federal education data. Here are scenes from the lives of teachers, before, during and after school.

ARRIVALS: Hope and heartbreak

The sun is rising, and teachers are arr